I have been a full-time professional sculptor working exclusively in hardwoods for over 47 years. I am self-taught. Carving flowers in wood has been the artistic passion of my life. The process consists of hand-guided bandsawing, hand-carving, and sanding of solid pieces of wood. There is no bending of the wood in any way. All pieces are one-of-a-kind and they are highly finished and beg to be touched. My work is unique in the art world.

The folllowing is an article from Down East magazine published in 1995.

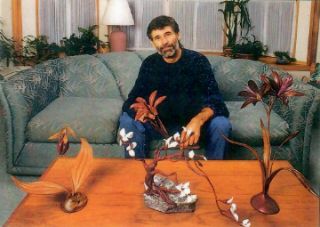

Sculptor David Pollock is used to people thinking that his flowers are the product of his garden. He is also accustomed to people breaking into tears at the sight of them. It is Pollock's special talent that he can fashion unbelievably delicate flowers - lady slippers and irises, lilies and roses - out of wood.

"Occasionally I get passed by at shows because people will think they're just looking at a bunch of flower arrangements, admits Pollock, who currently divides his time between his Fayette retreat west of Augusta and a home-studio in Scarborough. "When they discover they're not real, the question they most often ask is. 'Are these really wood?"

His flowers. so graceful and lifelike that they have adorned the windows of Tiffany & Company in New York City, really are wood, and nothing but wood, from native apple, cherry, and walnut to exotic rosewood, purpleheart, and granadillo. Somehow Pollock captures the softness of a petal and the grace of a stem in a medium more suited to flooring and furniture.

Pollock was first fascinated by the possibilities of wood as a child, and he left his former profession as a social worker fourteen years ago to devote himself full time to carving. Early on he developed a lucrative trade in low-end functional pieces such as cooking utensils, earrings, and lamps. But salad tongs and jewelry blossomed into an upscale business where the world of crafts met the world of art after he discovered his unique ability to carve flowers.

Today Pollock's pieces sell for up to $17,000. Tiffany's paired his work with a single piece of exquisite jewelry in each of its Fifth Avenue windows. His flowers grace the homes of such patrons of the arts as Charles Moritz. chief executive officer of Dunn and Bradstreet, and Arthur Sulzberger, chairman of both the New York Times and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In his salad days, Pollock's earrings sold for twelve to twenty-five dollars. Today Tiffany's is interested in a line of jewelry in the thousand-dollar price range. and Pollock is currently designing brooches in collaboration with his partner outside the studio, social worker Barbara Kinney.

Pollock's talent lies in being able to carve his wood "potato chip thin," as he puts it. The laborious process begins with a block of wood and a band saw, proceeds to detail work with a flexible-shaft power tool for carving out grooves, and then plateaus with what Pollock wryly refers to as the "fun part" - sanding, sanding, and more sanding. Surprisingly, Pollock finishes even his wispiest pieces with a power tool, using, successively finer bits, delicately removing individual layers of wood and letting the flower emerge. "It's all done by feel at that point," he said.

Pollock then fits his petals, stems, and leaves together with glue. Many admirers assume Pollock forms his pieces through steam bending. but with rare exceptions it's not that easy. "Wood has its own integrity," he explains. "Once you start scooping something out, if you tried to bend it the edges would crack."

Because each creation demands such detailed carving, he may put in up to 200 hours on one flower, and in a year he generally makes no more than a dozen pieces. Pollock has won accolades in the craft-show world, including a blue ribbon at the New England Spring Flower Show and Best of Show at the WBAI Holiday Crafts Fair at Columbia University in New York City. He recently finished an exhibit at Boston's presti gious Society of Arts and Crafts. Yet the "craft" designation rankles.

"There's a perception that art is not done in wood," he observes, a trace of annoyance in his usually soft-spoken voice. "There's a certain kind of snobbery about what art is. Metal is one of those acceptable materials. A gallery owner once told me that if I cast my flowers in bronze they would seem more like art. The first thing I thought was that she was nuts. To me the wood is very important. But after I thought about it. I took it as a compliment. She was seeing it as pure sculpture, in terms of line."

The art-versus-craft debate is not an issue at Tiffany's. "You're talking about one of my favorite artists," declares Gene Moore, vice president and display director. "I don't feel wood when I look at his flowers; I feel what he tries to show me about nature. It's absolutely magic."

"Some people have stood in front of certain pieces and started to cry." Pollock says. "I think there is something there that does hit people on an unconscious basis, and that is what art is supposed to do."

Pollock grew up in Biddeford, where his mother struggled to make ends meet as a single parent whose battle with arthritis prevented her from working outside the home, and he is a typical stubborn Mainer. He insists he will continue to work in the practical, no-nonsense medium of wood, despite what some New York City gallery owner may tell him.

"I have a real affection for wood," he explains. "There are some new woods at the wood store, and it's driving me nuts because I've been wanting to work with them. The initial process of cutting the slabs before they are carved and seeing the grain as it comes out of that just real- ly turns the on."

While Pollock is making a name for himself in New York City, his own aspirations have nothing to do with life in the urban fast lane. In fact. even Scarborough is getting too cosmopolitan for him, and he looks forward to moving to his home in Fayette permanently next year. "My dream is to be more self~sufficient," he says, "to make the carving the cash crop of the homestead trip - that whole sixties hippie thing."

What reason could he have for retreating to the isolation of western Maine, purposely putting himself at even greater distance from his most promising market? Pollock contemplates the question as he sits on the back deck of his lovingly restored eighteenth-centuty farmhouse, the sun catching the waves on nearby David Pond, his dog Molly chasing chipmunks on the lawn, "This is it right here, You're looking at it," he says.

In Pollock, the independent! spirit of a Mainer blends nicely with the independent spirit of an artist. He is determined to continue doing what he wants to do for those who appreciate him. "I'm only trying to affect one person with each piece. It's very freeing in that way. It only has to be very important to me and to the person who buys it."

Because of the amount of detail each blossom (and each petal) requires, Pollock rarely completes more than a dozen pieces each year. But the finished works can fetch prices as high as $17,000 in New York, allowing him to live a comfortable, back-to-basics life in Scarborough and Fayette.

Photographs by Randy Ury